|

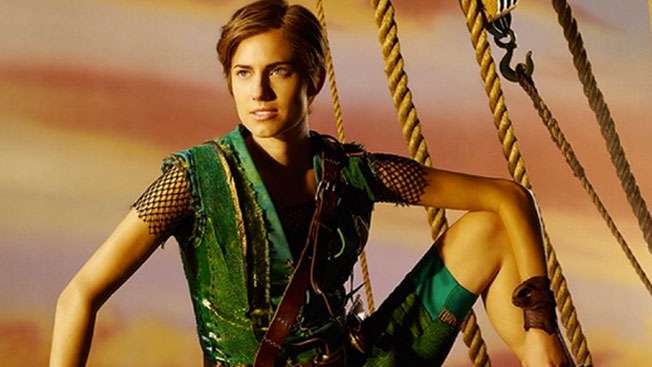

| Okieriete "Oak" Onaodowan as Pierre in Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812. |

But shortly thereafter, a vocal segment of Twitter cried foul, as Patinkin's surprise Broadway return meant that the production's current Pierre, Okieriete "Oak" Onaodowan, would be cutting his run in the role short barely a month after taking over for original leading man Josh Groban. Many questioned if there was a racial motivation behind asking a black actor to step aside for a white performer, and Onaodowan for his part made it clear that he was turning down the producers' invitation to return to the show after Patinkin finished his run. Although nothing was explicitly said, one gets the impression there's some bad blood between Onaodowan and the producers over the way this was handled, and that Onaodowan's departure wasn't the mutual agreement it was made out to be in the initial press release. The famously principled Patinkin subsequently withdrew from the production on Friday, stating that he would never knowingly take a job that would harm another actor.

Now, a couple of clarifications. I don't think Onaodowan is out of line to be a bit perturbed by the way this was handled, and I admire Patinkin's integrity in withdrawing from the show as a public rebuke to the producers. But the cries of this casting being in any way racially motivated strike me as bullshit, and I think those arguing otherwise are doing a huge disservice to the important and necessary conversation around diversity in the theatre.

Let's not forget that the producers of The Great Comet have gone out of their way to cast ethnically diverse actors from day one (they've even won awards for it). The lead role of Natasha has been very pointedly *not* white from the start, being originated by Chinese-American actress Phillipa Soo Off-Broadway before the beautifully dark-skinned Denee Benton took over for the show's Broadway transfer. The producers also had no problem casting Amber Grey to play the sister of the very Aryan Lucas Steele, and the ensemble is full wonderfully diverse performers that many casting directors would argue have no business being in a show set in 17th century Russia. These are all conscious choices that show the producers obviously care about representation; it makes no sense for them to suddenly decide ethnic performers can't lead their show.

What happened here is simply a case of needing a name to drive ticket sales. As composer Dave Malloy admitted on Twitter Friday, the show's advance sales have taken a nosedive since multiplatinum recording star Groban departed the show earlier this month. Well known singer-songwriter Ingrid Michaelson was brought in to play the key supporting role of Sonya the day after Groban left to help boost ticket sales, a move that seems to have worked in the short term. (It should be noted that Michaelson's casting resulting in another performer taking a leave of absence from the show and no one batted an eyelash.) Patinkin's scheduled start date the day after Michaelson's departure was an obvious attempt to keep the show running with ticket sales high.

It is a classic example of the problem with star casting, as shows built around a particular performer have difficulty sustaining interest once said performer leaves. (For an extreme example, the smash hit revival of Hello, Dolly! lost over $1 million in ticket sales when Bette Midler went on vacation earlier this month.) Great Comet was sold from day one as a Josh Groban vehicle, perhaps understandably so. Can anyone imagine the oddball, immersive show securing a prime theatre like the Imperial and running for months at near capacity without a big name to put butts in seats? The producers' gamble clearly worked.

What they realized too late was that they had no idea how to sell the daring, somewhat divisive show without a star who has a huge, devoted fanbase willing to spend big bucks to see him or her. Patinkin's wide exposure thanks to roles on high profile television shows like Homeland and Criminal Minds - not to mention a beloved supporting turn in the movie The Princess Bride - gives him significantly box office draw than a talented but little known performer like Onaodowan. (Yes, Onaodowan was in Hamilton, but he didn't star in Hamilton, and the Pultizer Prize-winning musical's continued sold out status proves that for that production the show is the draw more than any individual actor.) A white actor with a similar resume would have found himself in the exact same position of being "asked" to step aside the moment Patinkin's schedule opened up.

And that is the reason why this mess still feels icky, despite the lack of racial motivation. Onaodowan was only scheduled to be with the show for 2 months to begin with, and he was unceremoniously dumped the second a bigger star came along. Further, the producers clearly fudged the truth when presenting the idea to Patinkin, making it appear as if Onaodowan had agreed to take a leave of absence rather than being forced out. What they didn't count on was the true story making its way to Patinkin, and the Tony winner changing his mind when he found out his new gig was forcibly taking a job from another actor who had already been promised a set number of performances.

So feel free to condemn the producers of Great Comet for this situation, but leave the accusations of racism out of it. It is dangerous to raise the specter of racism in a case where that clearly wasn't the intent. Crying wolf on a matter as important as the treatment of black performers will make it that much more difficult to get people to pay attention when true injustices occur. It will be easier to discount complaints about mistreatment as fabrications, and it could well discourage other productions from going after diverse casts if they feel it is a "no win" situation. We need to encourage and educate our allies, not dismiss them after one unintentional misstep.